When Boris Johnson won the Conservative Party leadership vote on July 23, markets hardly flinched. At the end of the day, the pound was only marginally lower (-0.3%) and the FTSE 100 was up half a percent. The obvious conclusion was that financial players had anticipated this outcome and the result was already priced in. Most now assume that Johnson’s victory will result in an increased risk of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit, so that has to be the base-case scenario going forward.

But what if the inconceivable now happens and—against all odds and the declared red lines of the European Union—the new Prime Minister manages to renegotiate the withdrawal agreement and then—even more astonishingly—gets it through Parliament? In other words: How can we model the impact of a ‘deal’ Brexit on financial markets and the associated risks?

Our go-to method in such a case is to use the stress-testing capabilities of our Axioma Risk™ platform. As we have stated many times before, a stress test requires two decisions: (1) which variable do we want to shock and by how much and (2) which (historical) period would be suitable to calibrate the correlations and betas for the remaining pricing factors?

Start with the pound…

The foreign-exchange rate is usually a good starting point, as it tends to be driven primarily by issues specific to the respective country or region—unless it is a major reserve currency, which sometimes tend to be influenced by wider, global concerns. This contrasts with share prices and benchmark sovereign yields, which are often influenced by their counterparts in other markets.

…which is likely to appreciate

It is probably safe to assume that a soft Brexit would have a positive impact on the value of the pound. When optimism on an amicable agreement was greatest after the initial negotiating successes in the autumn of 2017, the pound recovered to $1.43. This would constitute a 17% appreciation from current levels against the USD, which we think is a realistic assumption over the 3 months to the end of October. We will therefore use this as the assumed shock in our stress tests.

Use historical precedents of Brexit optimism for calibration

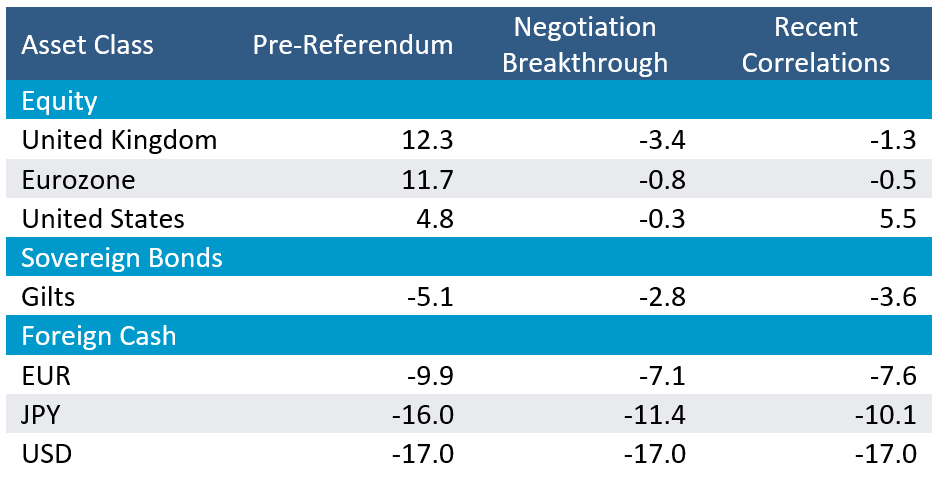

In order to estimate the impact of such a GBP appreciation, we use two historical periods and current cross-asset class correlations. As the first calibration period, we propose the 3 months leading up to the Brexit referendum. This time span was characterised by a simultaneous rise in UK share prices and the value of the pound under the expectation that the decision would be in favour of remaining in the European Union. The second historical interval would be early November 2017 to late January 2018, when the first ‘breakthroughs’ were reached in the withdrawal negotiations, and GBP/USD rose all the way to $1.43 in anticipation of an amicable separation. Finally, we analyse the same scenario using correlations and betas over the past 3 months. The impact on various asset classes is shown in the table below.

Simulated Asset-Class Returns

The first thing we notice when looking at the stress-test results is the discrepancy between the projected stock-market performances in the three scenarios. When applying pre-referendum correlations, a GBP-appreciation seems to go hand in hand with a surge in UK share prices. We have repeatedly argued in previous blog posts that a hard Brexit would result in a simultaneous drop in both GBP/USD and the British stock market, and we stand by this prediction. Yet, the reverse argument is not as straightforward.

UK shares could underperform foreign competitors

Over the past 3 years, we have also consistently noted an inverse relationship between the pound and the FTSE index, the argument being that a weaker exchange rate would be good for British exporters and vice versa. It is therefore conceivable that UK companies could still underperform their Continental European and North American competitors, despite a more favourable economic outlook. Note, though, that we formulated this as a relative rather than an absolute performance, as much of global stock-market movements over the next 3 months will depend on what the Federal Reserve Bank does.

Gilt prices fall as risk appetite returns and BoE raises rates

Gilts, on the other hand, showed a consistent negative return throughout. We think this is a reasonable assumption for two reasons. First, an increase in risk appetite is likely to reverse some of the recent flight-to-quality flows into government debt. Second, Bank of England officials have repeatedly stressed that the main reason preventing them from raising interest rates so far has been the ongoing Brexit uncertainty. If the latter is removed and an advantageous deal is struck, the Bank may still make good on its promise.

Hard Brexit is not a foregone conclusion

The recent further depreciation of the pound, following comments from Boris Johnson and his new cabinet of hard-core Brexiteers, seems to indicate that financial markets still consider a no-deal exit the most likely scenario. Yet, it is not a foregone conclusion. There is still a large cross-party opposition in Parliament, which fiercely opposes a hard Brexit or is even against leaving the European Union at all. There is also the possibility of a successful vote of no-confidence against the new Prime Minister, which would, in turn, trigger a new election and, most likely, further delays in the departure date. And there is still the chance—however remote—that politicians can at last agree on a solution that works for everyone. Bottomline? Be prepared!