In capital markets investing, the greater fool theory1 states that an investor buying a risk asset, no matter its current valuation, can always find a “greater fool” to buy it later at a higher price. The theory rests on the subjectivity of valuations and the fact that beauty (the attractiveness of the investment) is always in the eyes of the beholder. Put another way, investors buy assets for multiple reasons; some because they want to, others because they have to (e.g., to stay within tracking error limits). As far as the greater fool theory is concerned, this is a distinction without a difference.

Taken to the extreme, the greater fool theory turns investors into speculators, buying risky assets based not on valuation, but on their confidence in being able to sell them later at a higher price. And the stronger their confidence, the higher the price they will pay for such assets.

In the age of quantitative easing, this greater fool has a name: the Federal Reserve2.

The unprecedented and open-ended asset-purchasing program launched by the Fed (and other central banks) in response to the impact of the Covid pandemic has turned investors’ confidence in finding a greater fool for risky assets to a near certainty. Granted, the Fed reluctantly took on the role of the greater fool for the benefit of the greater good. But that does not alter the fact that, in doing so, the fundamental focus of investing shifted from owning to selling. These are the perfect circumstances for asset bubbles to grow—and grow and grow3. The problem is that bubbles have been known to burst, and sometimes spectacularly so.

What happens when the Fed assumes the role of the greater fool?

Using the Quality factors in the new Qontigo Factor-based Fixed Income Model (FFIM), we look at investors’ behavior before and after the Fed’s announcement of its vigorous asset-purchase program. As mentioned by my colleague Christoph Schon in his research paper titled “Bonds have style, too: A new model for capturing fixed-income risk premia…and much more”, the four Quality factors represent,

“…a quartile of the cross-sectional distribution of spread levels of all issuer curves in the respective currency. An issuer’s exposure to the appropriate factor is determined by its curve’s percentile in the cross-sectional distribution. Most curves will be exposed to two quality factors (with the weights assigned through linear interpolation between quartile buckets), except those at the high and low ends of the quality distribution.”

In this example we focus on the investment-grade segment of the USD senior corporate bonds from North American issuers, across all sectors ex-financials. Mapping the four quality factors with the median agency ratings we find that BBB ratings (the lowest rating in the investment-grade segment) makes up about 85% of the 2nd quartile (Q2) and 96% of the 3rd quartile (Q3) for investment-grade bonds—i.e., those available to institutional investors.

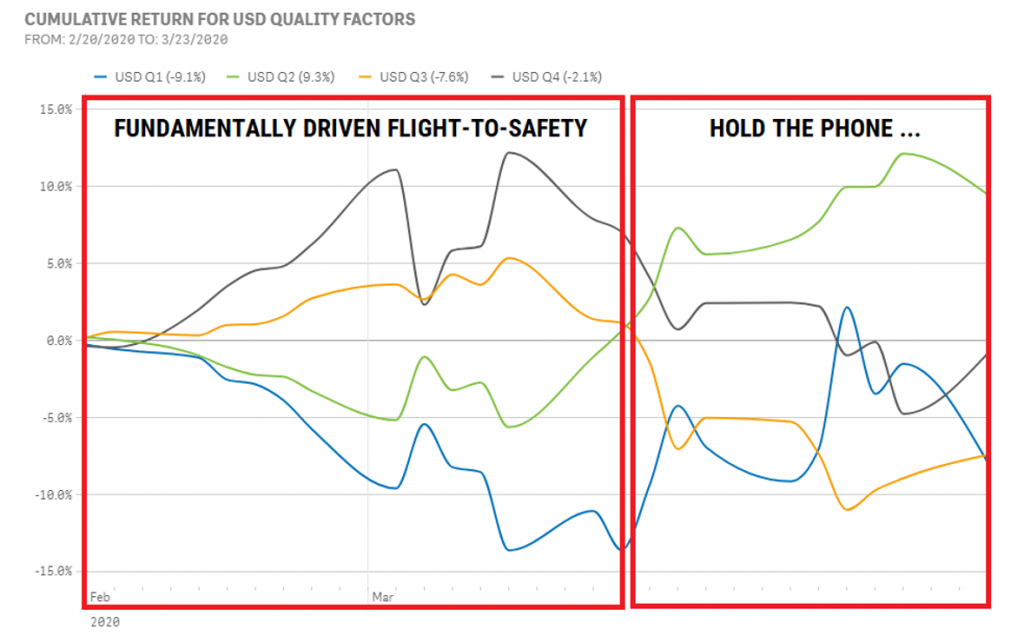

The chart below shows the cumulative return of the four Quality factors between February 19, 2020 (pre-COVID-19 peak) and March 23, 2020 (bottom of COVID-19 crash). As noted in the above-mentioned paper,

“The returns are in excess of the corresponding currency intercept, with Q1 representing the “best quality” issuers with the tightest spreads and Q4 those with the highest risk premia. A rising line implies that spreads in the quartile widened more than the currency average, while a falling graph signifies a relative tightening.”

In this chart we illustrate the traditional flight-to-safety response of investors to the COVID-19 pandemic. Initially, the blue (Q1) and green (Q2) lines representing the highest quality bonds decline, signifying a tightening of the spread for these issuers as investors flee to quality. The orange (Q3) and black (Q4) lines rise as investors sell lower quality bonds. But in mid-March the Fed intervenes with quantitative easing and asset-purchase programs on an unprecedented scale.

This throws investors’ flight-to-safety strategies into reverse (the “Hold the Phone” phase in the chart). The blue (Q1) and green (Q2) lines now rise, while the orange (Q3) and black (Q4) lines decline as investors realize there is now a greater fool in the market. Other central banks follow suit, and more details are provided regarding assets participating in the central bank’s asset-purchasing program.

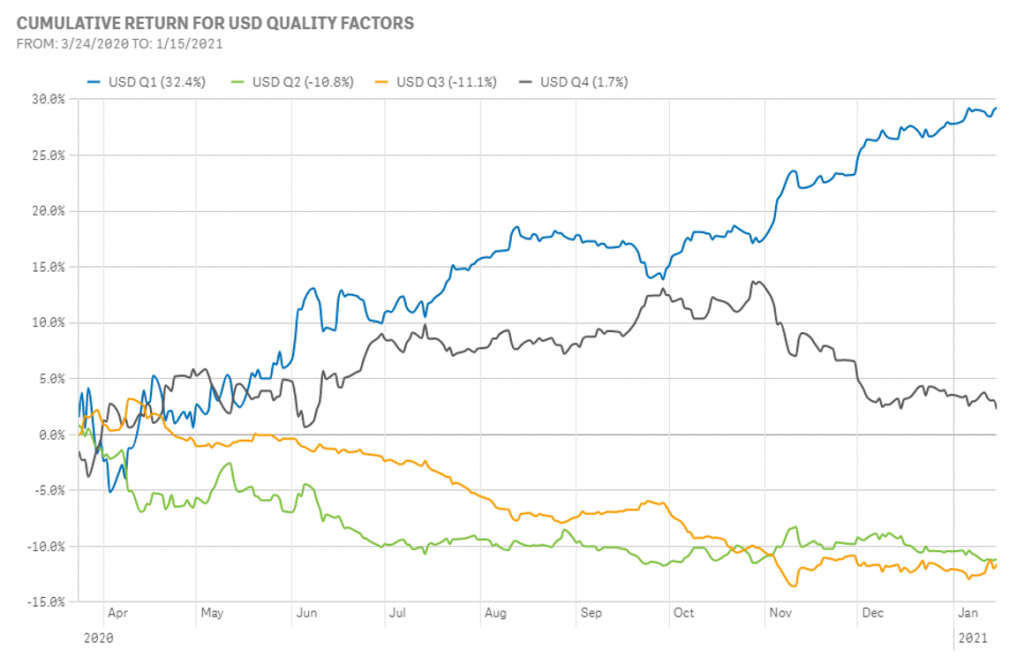

The chart below shows investors’ behavior since the announcement (March 24, 2020 to January 15, 2021). After combing through the details released by the Fed, investors have focused their attention on Q2 & Q3—the so-called fallen angels. The green (Q2) and orange (Q3) lines trend lower for the entire period, while the blue (Q1) line trends upward. Investors have also decided that the black (Q4) line would not benefit from this program and stayed away from those lowest quality bonds, until November when news of multiple COVID-19 vaccines signaled a potential end to the pandemic and its economic impact in the not-so-distant future, making investors return to bargain hunting in that segment.

The pandemic has lasted longer than anyone expected. Social distancing and other measures are still being enforced across the globe and the damage to the global economy is ongoing with no clear end in sight. Yet, the valuations of the most vulnerable segments of the corporate bond market have been rising since April 2020 in complete disregard for rising defaults risk among those issuers. The reason for this behavior is that the Fed has underwritten default risk with its near-zero interest rates and presented itself as the greater fool to investors.

To be sure, this (over)confidence in finding a greater fool is not limited to bond investors. Looking at factor returns in Qontigo’s fundamental factor model (US4-MH) for the US equity market, the 2020 return to the US Market Sensitivity factor was more than 12%—almost twice the return of the next-highest year. This highly positive return, which suggests investors were clamoring for the highest-beta names and shunning the lowest, stands out against the backdrop of a negative long-term average for this factor and only a 35% chance of a positive return (based on the 39 years of the US model). The Volatility factor’s nearly 13% gain in 2020 also points to a risk-taking bubble. Its annual return was positive in only six of those 39 years, the most recent being 2009, and the average over our full history is even more negative than Market Sensitivity’s. It seems equity investors are also highly confident in finding a greater fool to bail them out of the highly risky, and increasingly richly valued, names they have chased since late March.

What can be said about the value of such programs and their potential costs?

The pandemic put the U.S. financial system at risk. As its guardian, the Fed had to step in and take measures to ensure its survival. But massive and open-ended asset-purchasing programs present their own set of potential long-term risks and consequences. For starters, as these programs get more effective, pervasive, and seductive, some investors begin to lose track of risk. This is dangerous because a transition back to normal times is ultimately inevitable. And the smoothness—or not—of that transition hinges on the preparedness of investors for when the bubble finally bursts. On days when investors have a high degree of confidence in finding a greater fool, the stock market rises with just your average sleepy volatility. But when this confidence drops, it resembles the fall of Saigon and many investors don’t make it out in time.

The Fed did its duty in taking on the role of the greater fool (again, for the benefit of the greater good). In turn, it is the duty of every investor to stay sharp—and never lose sight of risk—as a return to “normalcy” is only to be found on the other side of an irrational exuberance.

1 More details can be found here, and here, and here…

2 For the US market. The greater fool in Europe is the ECB, in the UK the BoE, in Japan the BoJ…

3 E.g. the price of Bitcoin these past few months!