Insights

From information to insights. Entering a new era of investment management

Insights

Want to challenge business as usual? Here you’ll find a collection of curated content on today’s leading topics, like ESG, data management, innovation and more.

Browse timely updates of market risk across a broad range of geographies and asset classes.

Equity Risk Monitors

Equity Risk Monitors

Latest trends in equity market risk.

Multi-Asset Class Monitor

Multi-Asset Class Monitor

Latest trends in and the impact on a global multi-asset class portfolio.

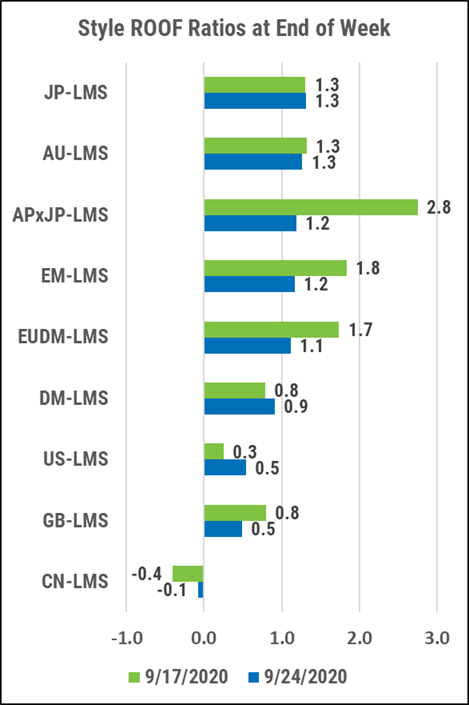

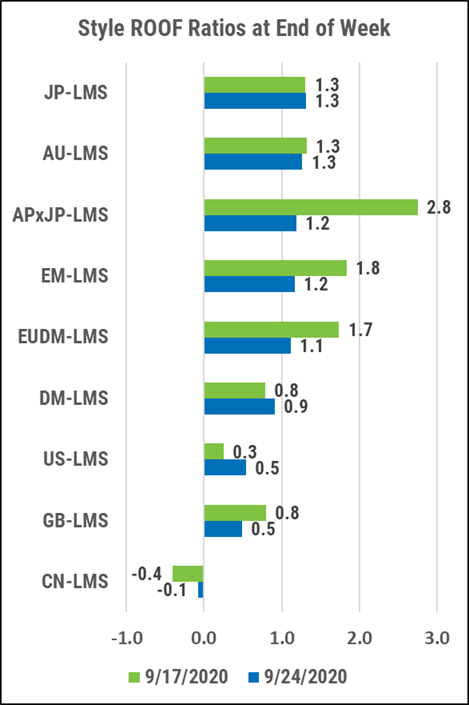

ROOF Market Sentiment

ROOF Market Sentiment

Review of investor’s risk sentiment, calculated using our Style and Sector multi-factor risk models.